The introduction of the new species has led to conversations on human-animal conflict — a problem that doesn’t always get the attention it requires.

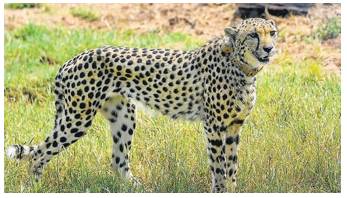

Cheetahs are back in India for the first time in more than 70 years. They are, however, not the Asiatic variety that once roamed large parts of the country — the species was declared extinct in India in 1952, a victim of unchecked hunting and habitat loss. Less than 100 of these animals survive in Iran today. On Saturday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi released eight cubs of the African species at the Kuno sanctuary in Madhya Pradesh. The animals were flown in from Namibia, which today has the highest cheetah population. The translocation has triggered a debate amongst conservation scientists with a section amongst them arguing that the 750 sq-km national park could limit the movement of the animals that prefer a much larger range. But others do not take such a pessimistic view and point to the cheetah’s adaptability across a range of habitats. PM Modi referred to the African big cats as the country’s guests. It’s up to the wildlife authorities to help these cheetahs make Kuno their home.

One of the spinoffs of this debate is the spotlight wildlife-related issues have received in the past few days. The introduction of the new species has led to conversations on human-animal conflict — a problem that doesn’t always get the attention it requires. Some of the successes of India’s wildlife protection programme have come at a cost. In several parts of the country today, humans and protected species live in proximity. Crop depredations and attacks on livestock — even humans — have become common. Only recently have studies begun to be undertaken on the carrying capacity of national parks and sanctuaries. They are yet to be used in a meaningful manner to restore a semblance of harmony between wildlife and people living in the vicinity of the protected areas (PAs). The problem gets compounded because developmental projects such as highways fragment the PAs, increasing the precarity of the animals who find it difficult to respect the new boundaries. A growing number of protected animals live in shrinking habitats with a dwindling prey base. This ecological imbalance requires redressal.

Kuno was originally earmarked for relocating lions from the Gir forests. But even as the Gujarat PA faces constant pressure on its carrying capacity, the state has obstinately refused to relinquish its status as the Asiatic lion’s sole habitat. Experts also say that confining the animal to one PA increases its vulnerability to epidemics. Wildlife protection must not be hostage to unscientific attitudes. The introduction of the cheetah is a moment that must be seized upon by policymakers to evolve solutions to such longstanding issues.