It was the summer of the 71. Agra, my hometown, was flooded. Our house, on a higher ground, was a bit less affected; nevertheless, water had entered the ground floor and we were perched on the top. As the rescue boats went by, we children were busy floating paper boats as playthings. They were, though inanimate, like our aspirations and thoughts. The boats, of course, couldn’t do a long course. But our imagination did. Those days we children had so much to do, so much to learn from the life around us that there was never a dull moment. Indeed! , for the children who spent their childhood around 50 years back, they had a childhood quite different from the current crop.

Innocence! That’s was all we had. The world around us was our playground. It was all real; there was nothing virtual about it. Yes, we children knew so little about everything else that was not in our immediate vicinity. But that was fun, exploring on our own and enjoying every bit of it. Unlike now, the phones were unheard of. We had wired phones instead, which we made with a thread and two matchboxes.

But the connections they provided were pretty strong. The parents at that time were different, too. They hardly cared what the child studied at the school unless a complaint from the school came in. They would often forget the standard in which their child studied. The only day the father would come into the picture was when you got your annual report card.

And his only concern was that if the child was promoted to the next class. Else, the ear-twisting took place. That was more or less summed the early education. Playing I Spy or Hit&Run was the best pass time. Children’s extracurricular activities involved spreading papads and chips in the sun. The packaged chips would come much later. Eating out meant having golgappas at the street vendor. Of course, the kulfiwala occasionally announced his arrival with a bell and we ran to have it.

Entertainment was hard to come by. We waited for the circus to arrive in town and made plans to go see it. We watched it with disbelief, often replicating the feat and hurting ourselves back at home. The melas were again something that we looked forward to. The charm, of course, was the merry-go-round and the giant wheel. It made us dizzy but then enjoyment doesn’t come cheap.

Those were the years of innocence and ignorance alike. As we grew up, we realised how little we knew about anything, yet we had learned so many lessons of life that stay with us forever. The parents did not care about the studies of their children; they cared about their health and so saw to it that the children ate everything cooked at home. The kids, too, contributed to the household chores willingly, or unwillingly in my case, but learned that anyway.

The elderly were no pariah either. The granny would tell endless ghost stories and we believed them all. For us, there was a ghost on every peepal tree, and the djinns, churails and dayans were watching us when we returned late. Caring for them came naturally, partly out of affection and partly out of greed for stories and money that the parents refused. There was a close bonding with them. They became part of you.

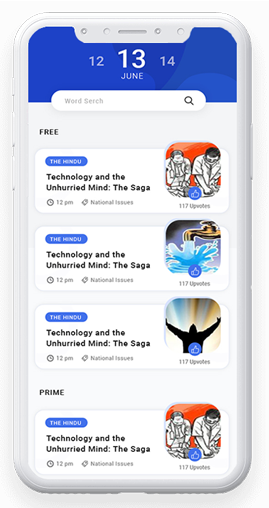

Now that when I see my kids growing, I realise the children and their childhood have undergone a sea change. They are informed but not innocent. They can get you the information you might have not known till your graduation. They don’t play with matchboxes or waste time decorating Janmashtami models. They are always with their gadgets. They play with them or, rather, live with them. Life has turned virtual. It is a digital degeneration of sorts where you know a lot yet you are rudderless as the framework that comes with human interaction is missing. The pizza-burger generation is more about flaunting its feat rather than enjoying it. The pictures of restaurants and places visited on the trip find floating on Instagram and Facebook. They might not see churails and dayans but have demons in their head which tell them to seclude them from the rest. You won’t know if your child is at home because he is too much engrossed with the mobile that he needs no one else.

Last year in the monsoon, I told my young daughter how we floated paper boats in the puddles. She said that she did not know how to make one. I was excited as she showed some interest. I said, I will make one for you. I made one, gave it to her, and asked her to set it afloat. Fifteen minutes later, she was with her phone again, chatting. I asked whatever happened to the boat she was supposed to play with. “It sank,” she said with a flat face and submerged into her phone again.